Exploration: Hot Spots, Hot Rocks, Emerging Themes

David Bamford

What do we see when we Examine the Global Exploration Picture?

Perhaps more than any other sector of the oil and gas business, exploration encourages rumour and anecdotes, with much important information being traded by ‘networking’. For example, sitting at lunch at a recent Finding Petroleum event, I learned more about the reported 2.5 billion barrel Johan Sverdrup oil discovery in Norway than I could attending a year’s worth of formal presentations!

Factual evidence is invaluable and so I was very pleased to get receive a copy of Richmond Energy Partners’ report on the exploration performance of 32 mid-cap and 8 large-cap E & P companies (outside North America) from 2008 – 2012.

I found a couple of their results especially compelling – before saying what they are, I need to take a little detour into some terminology:

There is a “Life Cycle” of exploration plays – Frontier, Prolific, Mature, “Red” – in which the status of any play can be considered.

In the early, Frontier, phase, there is only expenditure with the emphasis on making one or more ‘play opening’ discoveries.

In the Prolific phase, value creation is at a maximum, as discoveries are large (typically, “Giant” accumulations of >250mm boe gross), and therefore F&D costs are spread over a large number of barrels.

In the Mature phase, value creation can still be good as discovery sizes reduce but technology application and cost reduction become important in order to enhance economics.

In the “Red” phase, value destruction is probable, occasionally inevitable, as success rates plunge, the very few discoveries are small, and costs escalate. Of course, it remains possible for a company to “win” during this phase but the number of “winners” is small, the number of “losers” very high!

To illustrate, the movement of the UKCS North Sea Brent (oil) province can be positioned over its 45+ year history: Frontier – in the 1960’s: Prolific – in the early 1970’s: Mature – in the late 1970’s and in the 1980’s: “Red” – today.

It is important to emphasize that the right level of analysis is the play level. It would be absurd to pretend that a whole region lies in the “Red” zone for example; indeed the Johan Sverdrup discovery demonstrates the power of ‘new play’ thinking even in a basin with a long exploration history.

Three Takeaways from the Richmond Report

1. There is a significantly higher probability of making a 100 mm barrel discovery in a Frontier play than a Mature play (in fact it is about 7.5 times more likely!)

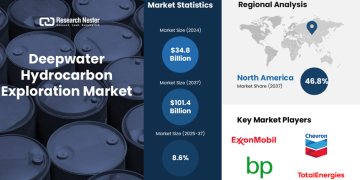

2. Overall, Frontier Exploration has been successful, with the 5 big ‘play openers’ all in Deep Water. For 2012, there is a huge focus on exploration drilling in the South Atlantic and East Africa (onshore and offshore).

3. In Frontier Exploration, there has been relatively little effort, and no discoveries, in stratigraphy older than the Cretaceous, whereas in Mature provinces, effort and discoveries reach down to the Devonian and older.

The first of these conclusions is obviously not a surprise, although the degree of difference may be to some.

The second and third points speak to Hot Spots and Hot Rocks respectively – let’s examine them in more detail.

Hot Spots

Taken together these two pictures illustrate the location of Frontier exploration efforts, the continuing importance of Deep Water, and the tendency of exploration companies to behave like a swarm of 8 year olds’ playing soccer – to be drawn magnetically to where the ball is!

Somewhat cynically, one might ask whether many companies are in fact pursuing their own exploration strategy or whether their approach is simply “Me too!”?

Hot Rocks

This picture raises an interesting question. It is pretty unlikely that prospective rocks in basins that are currently Frontier are restricted to plays in the Cretaceous and younger – evidence from this picture and exploration history in general is that as a basin Matures, insight and innovation will lead to a breakthrough in understanding – and therefore discoveries – in older rocks.

The question which follows is – what insights and what innovations? How do we get to them?

Nowadays, explorers are by and large are engaged in the search for new plays in known basins, plays of increasing subtlety and complexity in basins that have been ‘open’ for a long time, where somebody may well have gone before them.

Here are just four of the questions that explorers might be trying to answer today:

1. Massive amounts of gas have been found offshore East Africa. Is there anywhere to go to find oil?

2. Where are the analogues for the much-talked-about Brazilian sub-salt successes? Are there any in the South Atlantic other than offshore Angola?

3. Where might big fields be hiding in the Deep Waters of South East Asia?

4. Is the North Atlantic really a poor relation compared with the South Atlantic?

And where, to tackle these questions, plenty of – sometimes huge amounts of – data are now available to explorers.

Satellites have delivered global bathymetry and topography; satellite gravity data shows us crustal thickness globally; some 200,000 exploration wells – that’s 200,000 ‘wildcats’, never mind appraisal, development production wells – have been drilled in the last 50 years or so; there are sea-bed cores; any government that is serious about its resources has a national data repository; there’s data from Geological Surveys; there’s a huge published literature… .and so on.

The ability of explorers to deliver the increasingly difficult job of spotting the next big play depends on their ability to sift, organise and understand this ‘Niagara Falls’ of available data, to solve what some have referred to as the “Big Data” problem – or opportunity, perhaps?

Deploying a deep understanding of plate tectonics and chrono-stratigraphy – understanding what gets deposited where and when – is the key process by which this is achieved, the “Know How” whereby opportunity is accessed.

What it is not about is simply banging in (yet another) regional 3D survey and believing that more and more sophisticated seismic interpretation can deliver all the answers.

In addition, there is an emerging question – can we anticipate the beginning of the end of the era of Deep Water exploration and, if Yes, where will explorers head for next?

Emerging Themes

Undoubtedly, the Arctic will occupy industry’s efforts for some time but in my humble opinion, we will see a return to Onshore exploration, as we realise that we truly do have the technology to turn any discovered resources into reserves, no matter at what depth and in what rock they are found. With the help of 3D and 4D seismic, horizontal drilling and hydraulic ‘fraccing’, the many reservoirs where we find oil & gas – from coal beds and shales through to high poroperm sandstones – and the many different qualities of oil & gas – from ‘sour’ gas through to light oil – can in principle be developed and produced – the question is simply at what cost?

But the finding is the key! And here we have an issue or at least a question? Have modern-day explorers lost the subtle exploration skills of their predecessors? Have they come to rely on regional 3D surveys?

Generally speaking, this is not possible onshore due to the prohibitive cost of land (and transition zone) 3D seismic data, and explorers have to recourse to a more traditional ‘focussing’ approach, in which a range of technologies – including the boot on human feet – come into play. The steps in this ‘focussing’ approach can be characterised as: is there any evidence of the components of a viable petroleum system in the region under study; is there any evidence at all of actual hydrocarbons – seeps that can be sampled for example; can suitable, preferably large, structures be envisaged or a ‘sweet spot’ prognosed in a shale gas or shale oil play; then, and only then, can 2D, or preferably 3D, seismic delineate prospects?

Surprising as it might be to modern geoscientists, our predecessors in countries such as Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Russia, the onshore USA did actually get out in the field, in fact they spent most of their time there, they hit rocks with hammers, they plane-tabled, they drew cross sections, and yes, they knew a seep when they saw one and sampled it.

They didn’t spend their life looking at computer screens!

Extensive field work can still answer significant questions during the reconnaissance phase of exploration: can we identify potential source, reservoir and seal rocks; are there any active seeps; following sound principles of structural geology including section balancing, can trapping structures be envisaged at depth?

And technology of course has its pace.

Many onshore areas have not seen recent exploration using modern technologies, in particular a suite of technologies that can be integrated both to understand geological setting and to choose well locations with precision.

These technologies all exist: the key to unlock the whole will be a step change in our ability to obtain onshore 3D seismic.

Who Will Succeed Onshore?

The lesson of history is that successful onshore explorers will combine entrepreneurial leadership with deep technical skills. My personal prejudice – cultivated firstly in BP and latterly in Tullow Oil – has always been that a company needs its own, dedicated, team of full-time petro-technical employees to achieve this.

However, examining the so-called ‘unconventionals’ boom in the USA indicates that this isn’t necessarily so, provided that entrepreneurial management can find a firm of consultants who can bring into play deep, broad, technical teams of experts who have ‘seen a lot of rocks’.

I have not yet seen evidence that such consultants exist in Europe. And for this reason, I find it difficult to highlight which European Hot Spots and Hot Rocks might be reported on in say 2 years’ time.